Biden Tax Law Proposal Targets High Income Individuals, S-Corps and Trusts

September 14, 2021

September Returns and Asset Performance

October 2, 2021New Tax Law Proposed Will Kill IRA Conversions and Investments in Private Placements

Introduction

The new tax law presented by Democrats seeks to reform retirement plan rules. It also seeks close “loopholes” commonly used by wealthy individuals. Finally, it limits private equity investments by IRAs, including business start-up funding. The list of changes is significant If you have an IRA or you will inherit one:

- First, the proposed law seeks to eliminate the ‘backdoor’ Roth strategy. Specifically, the law stops traditional IRAs from converting to Roth IRAs using after-tax funding.

- Second, a rule change would prohibit all Roth conversions (involving other retirement accounts) for those in the top income tax bracket.

- Third, the law would prohibit IRA contributions by high-income taxpayers if the tax-deferred accounts have over $10 million.

- Fourth, the law imposes a 50% Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) on balances above $10 million. It also imposed a 100% RMD on combined balances above $20M. The result is to force dollars out of tax deferred havens.

- Fifth, new rules will kill the ability of taxpayers to place private placements in IRAs.

- Finally, new rules eliminate ‘defective’ Grantor Trusts, as explained below.

Congress will finalize the legislation known as Responsibly Funding Our Priorities in the weeks to come. The proposal creates planning opportunities for sure. However, the planning windows will close quickly. Read on for more details.

Prohibition on On Roth Conversions

If enacted, Section 138311 of the proposal is going to break some hearts. The provision would prohibit conversions of after-tax dollars held in retirement accounts beginning in 2022. The new rule applies to both IRAs and employer sponsored plans. As a result, the “Backdoor Roth IRA,” and the even more powerful “Mega-Backdoor Roth IRA,” would come to an end.

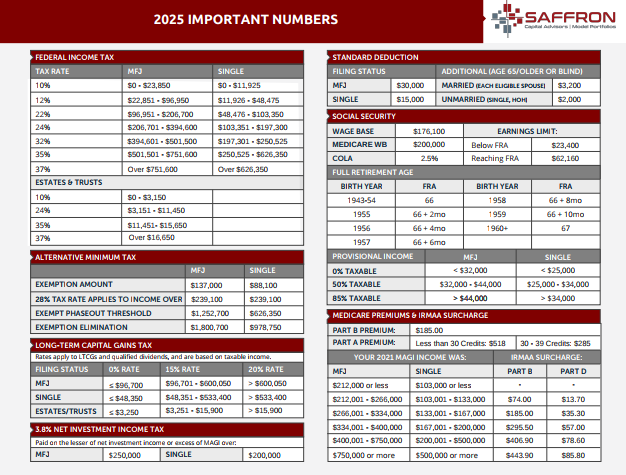

Under current law, contributions to Roth IRAs have income limitations. For example, the income range for single taxpayers for making contributions to Roth IRAs for 2021 is $125,000 to $140,000. For example, single taxpayers cannot make Roth contributions if their income is above $140,000. However, in 2010, Congress repealed the income limitations and allowed anyone to contribute to a Roth IRA through a conversion. As a result, he or she can make a nondeductible contribution to a traditional IRA, and then convert the funds from the traditional IRA to a Roth IRA after paying tax. Taxpayers pursue conversions when their future taxes rates are expected to be higher. For many, that is often the case due to forced liquidations of IRAs under the tax code.

The bill eliminates Roth conversions for single taxpayers (or taxpayers married filing separately) with taxable income over $400,000. The limit is $450,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. Heads of households have taxable income limit of $425,000. This provision applies to distributions, transfers, and contributions made in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2031….yes, that’s 2031.

Really?

“Why in the world would they delay the effective date so long for something they clearly want to ban?” The answer is simple. As the popular expression goes, “Follow the money!” By keeping Roth conversions on the table for another decade, legislators are encouraging high-income taxpayers to convert to Roth accounts. In effect, they want you to pay taxes sooner rather than later. At the same time, legislators can count on the income from those conversions for budget projections for another 10 years!

New Funding and Contribution Limits for IRAs

Under current law, taxpayers may make contributions to IRAs irrespective of how much they already have saved in such accounts. The legislation creates new rules for taxpayers with very large IRAs and retirement account balances. In effect, the law seeks stops subsidies in the form of tax advantages once account balances reach a certain level.

Specifically, the law prohibits contributions if the account exceeds $10 million at the end of the prior tax year. The limit on contributions would only apply to single taxpayers (or taxpayers married filing separately) with taxable income over $400,000, married taxpayers filing jointly with taxable income over $450,000, and heads of households with taxable income over $425,000 (all indexed for inflation).

The legislation also adds a new annual reporting requirement to the IRS for employer defined contribution plans on aggregate account balances in excess of $2.5 million. The provisions of this section are effective tax years beginning after December 31, 2021.

New Required Minimum Distributions For Taxpayers With High Income

The new law creates new minimum distributions if combined retirement account balances generally exceed $10 million. The distribution impacts taxpayers with income above thresholds (e.g., $450,000 for a joint return). The minimum distribution generally is 50 percent of the amount by which the individual’s prior year aggregate traditional IRA, Roth IRA and defined contribution account balance exceeds the $10 million limit.

In addition, to the extent that the combined balance amount in traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs and defined contribution plans exceeds $20 million, that excess is required to be distributed from Roth IRAs and Roth designated accounts in defined contribution plans up to the lesser of (1) the amount needed to bring the total balance in all accounts down to $20 million or (2) the aggregate balance in the Roth IRAs and designated Roth accounts in defined contribution plans. Once the individual distributes the amount of any excess required under this 100 percent distribution rule, then the individual is allowed to determine the accounts from which to distribute to satisfy the 50 percent distribution rule above.This provision is effective tax years beginning after December 31, 2021.

Prohibition of IRA Investments Conditioned on Account Holder’s Status

The bill prohibits an IRA from holding any security if the issuer of the security requires the IRA owner to have certain minimum level of assets or income, or have completed a minimum level of education or obtained a specific license or credential. For example, the legislation prohibits IRAs from holding investments which are offered to accredited investors because those investments are securities that have not been registered under federal securities laws. IRAs holding such investments would lose their IRA status. This section generally takes effect for tax years beginning after December 31, 2021, but there is a 2-year transition period for IRAs already holding these investments.

Prohibition of Investment of IRA Assets in Entities in Which The Owner Has a Substantial Interest

The new law seeks prevents an IRA owner from investing his or her IRA assets in a corporation, partnership, trust, or estate in which he or she has a 50 percent or greater interest. The goal is to avoid self-dealing. However, an IRA owner can invest IRA assets in a business in which he or she owns, for example, one-third of the business while also acting as the CEO.

The bill adjusts the 50 percent threshold to 10 percent for investments that are not tradable on an established securities market, regardless of whether the IRA owner has a direct or indirect interest. The bill also prevents investing in an entity in which the IRA owner is an officer. This law would takes effect for tax years beginning after December 31, 2021, but there is a 2-year transition period for IRAs. Taxpayers must modify or liquidate prohibited investments during the two year period.

New rules for ‘Defective” Grantor Trusts

The Internal Revenue Code treats trusts inconsistently. As a result, the proper taxation of assets held in trust is not clear. The intent of trusts is to create an entity that is taxed separately from the original owner of the trust assets. This simple goal can be achieved, but is prone to tax abuses when individuals shift assets to a trust in name, but not in substance.

To address this problem over the decades, Congress enacted a series of provisions to determine how to hand trusts. For example

- a trust is treated as the grantor’s for income tax purposes (known as the “grantor trust”) under IRC Sections 671-678,

- trusts are treated as the original grantor’s for estate tax purposes under IRC Sections 2031-2046,

- a trust allows a retained interest under IRC Section 2036

- trust are revocable in certain conditions as defined by IRC Section 2038.

The legacy rules have inherent flaws. For example, a grantor can place assets in trust that he owns for income tax purposes, but not for estate tax purposes. This creates the possibility for a “defective” grantor trust. In response, the new tax law pulls grantor trusts into a decedent’s taxable estate when the decedent is the deemed owner of the trusts. Prior to this provision, taxpayers were able to use grantor trusts to push assets out of their estate while controlling the trust closely. The provision also adds a new section, which treats sales between grantor trusts and their deemed owner as equivalent to sales between the owner and a third party. The amendments made by this section apply only to future trusts and future transfers.

If you have questions, you can contact me here.